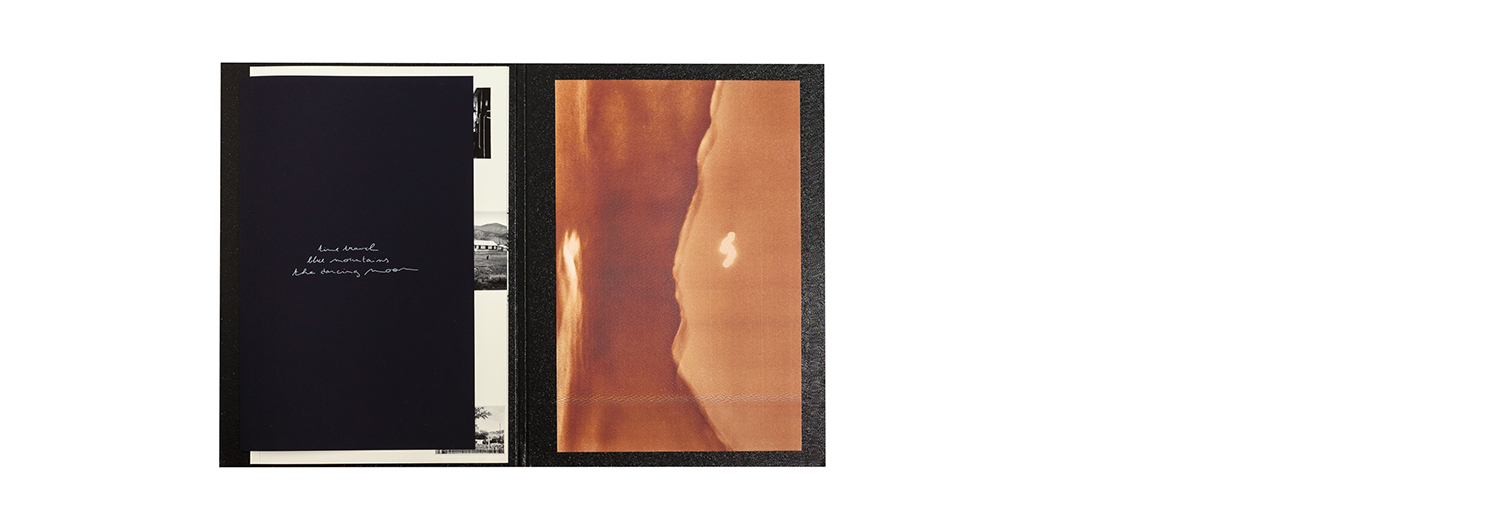

Anthony Prevost

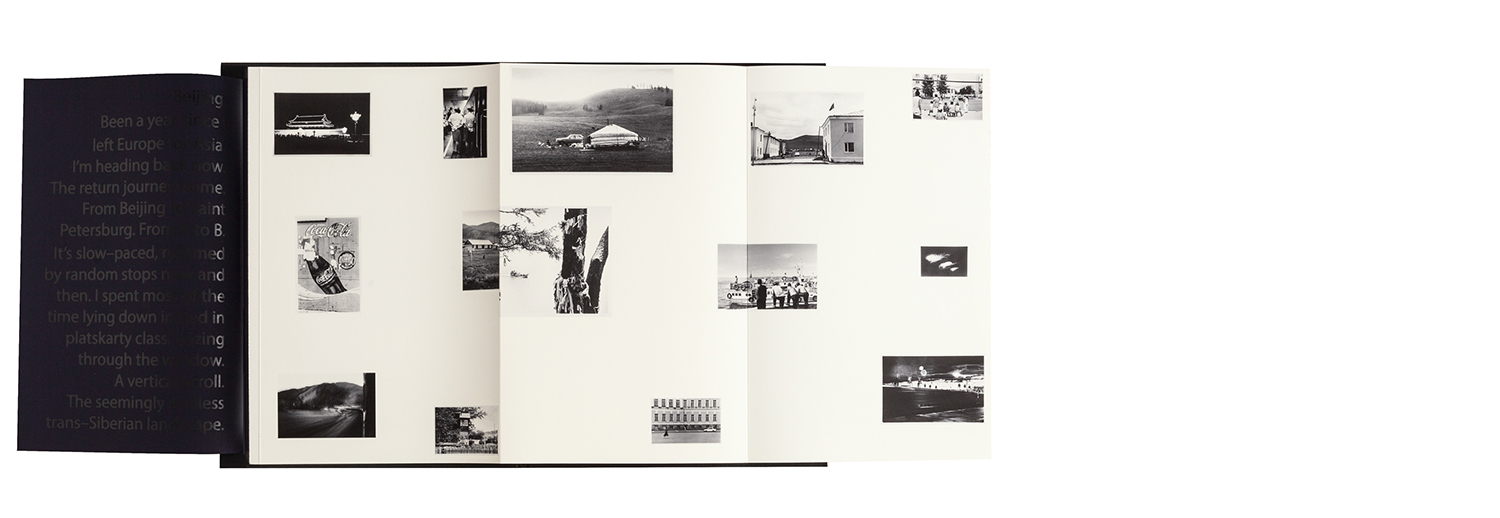

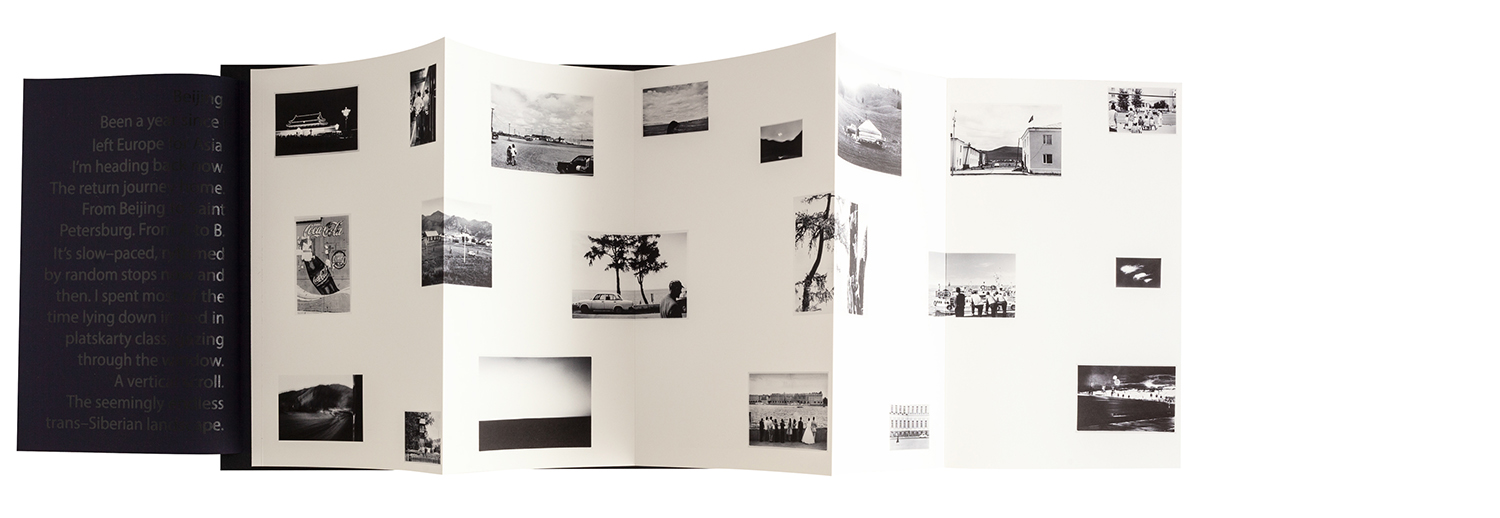

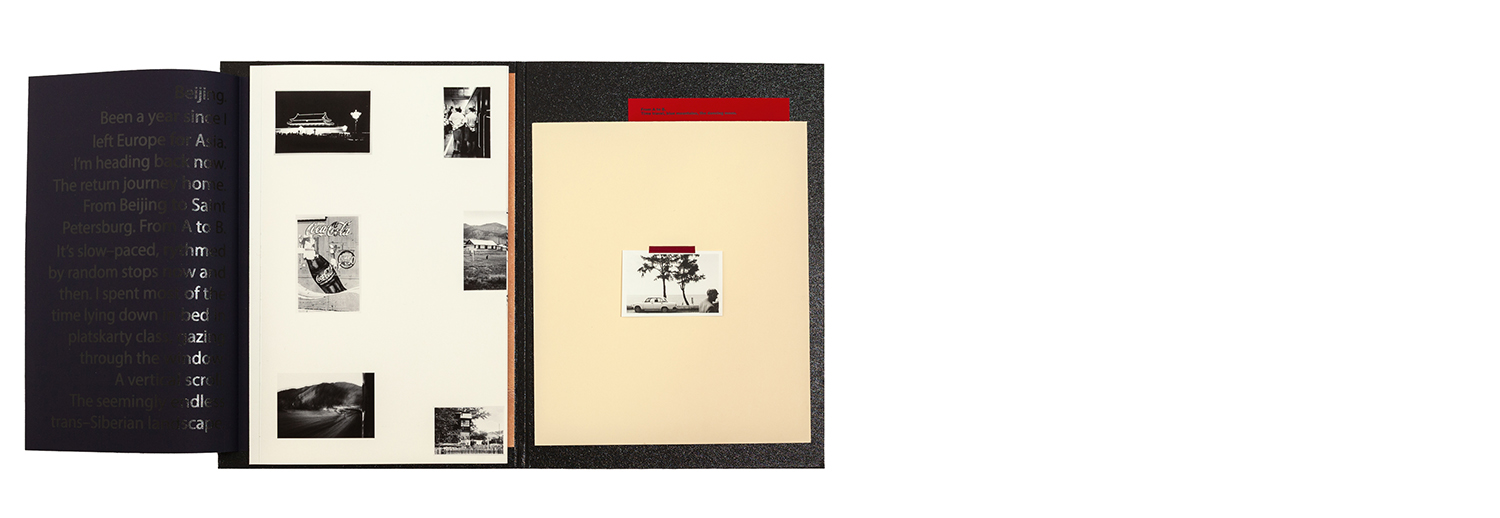

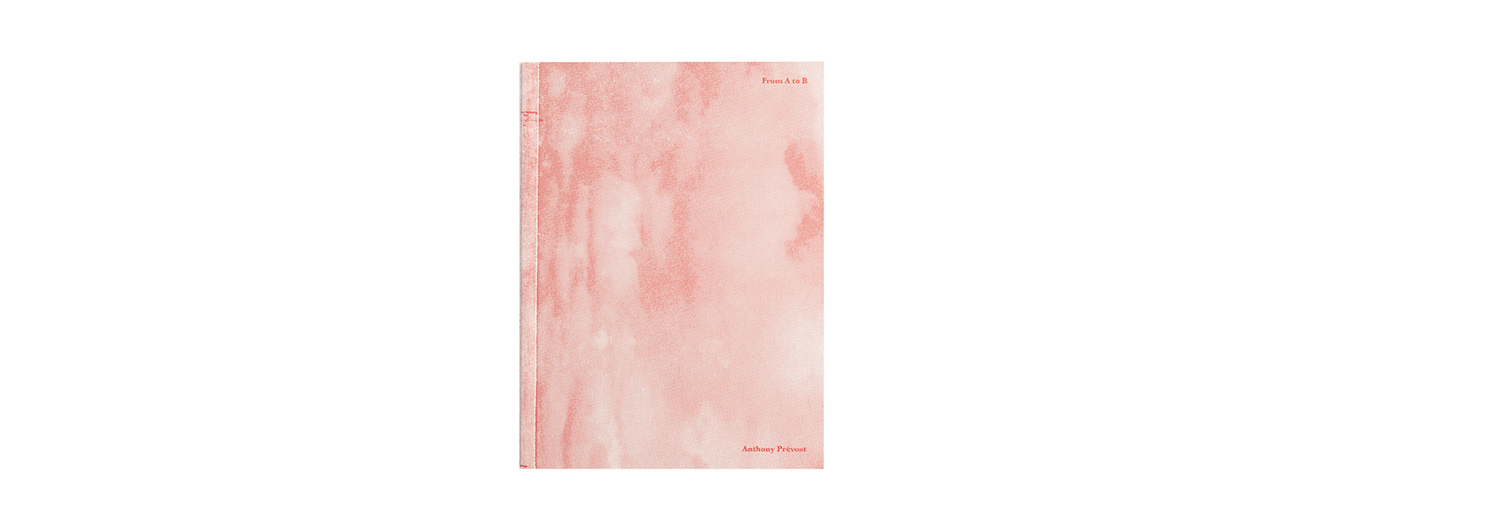

FROM A TO B –

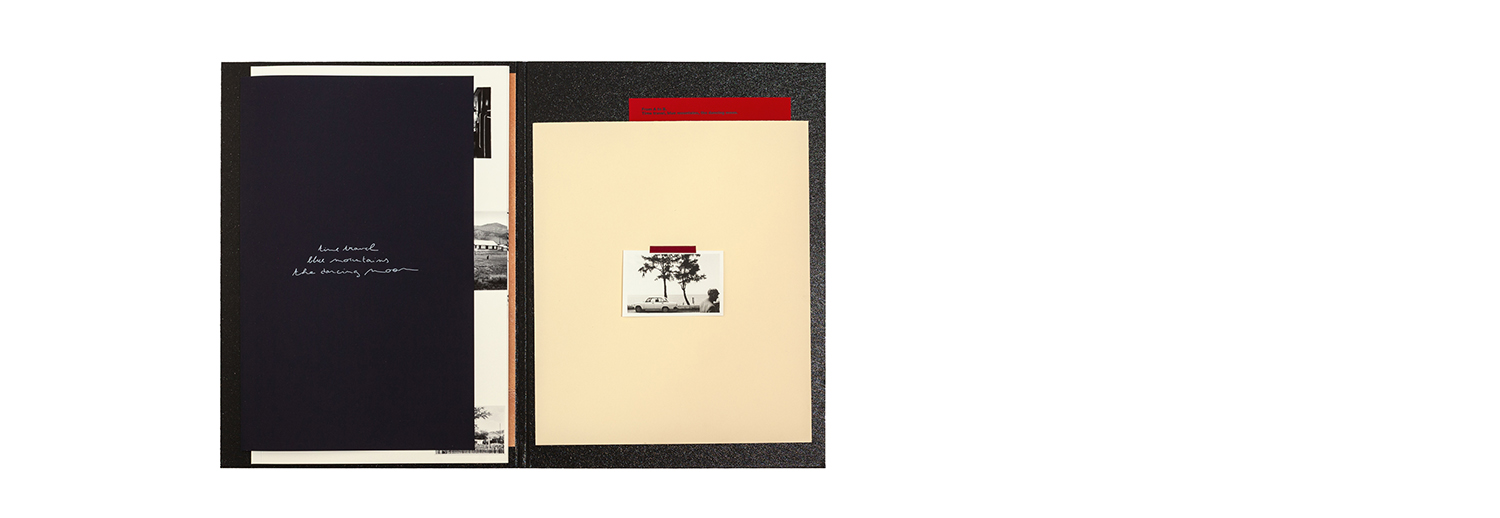

Time travel, blue mountains, the dancing moon

(artist book | 2019)

From Beijing to Saint-Petersburg.

Photographs, text, and song from the Trans-Siberian / Trans-Mongolian railway.

Concertina book pigment ink print on natural white paper

One gelatin silver print on baryta paper base – handprinted 2014 | ed 9 + 2 AP

(approx size – image: 8 x 5,5 cm | mount: 23,5 x 27,5 cm) signed & numbered

Book-cover screen printed on archival grey boards

Title sheet screen printed on GF Smith Plike paper with glossy ink

Double-sided laser print on blotting paper

Mongolian folk song laser print

Text from Eugenie Shinkle

Made and published by the artist, London 2019. Size: 35 x 25 cm

Edition 40 + 2 AP Comes signed & numbered

Book conversation

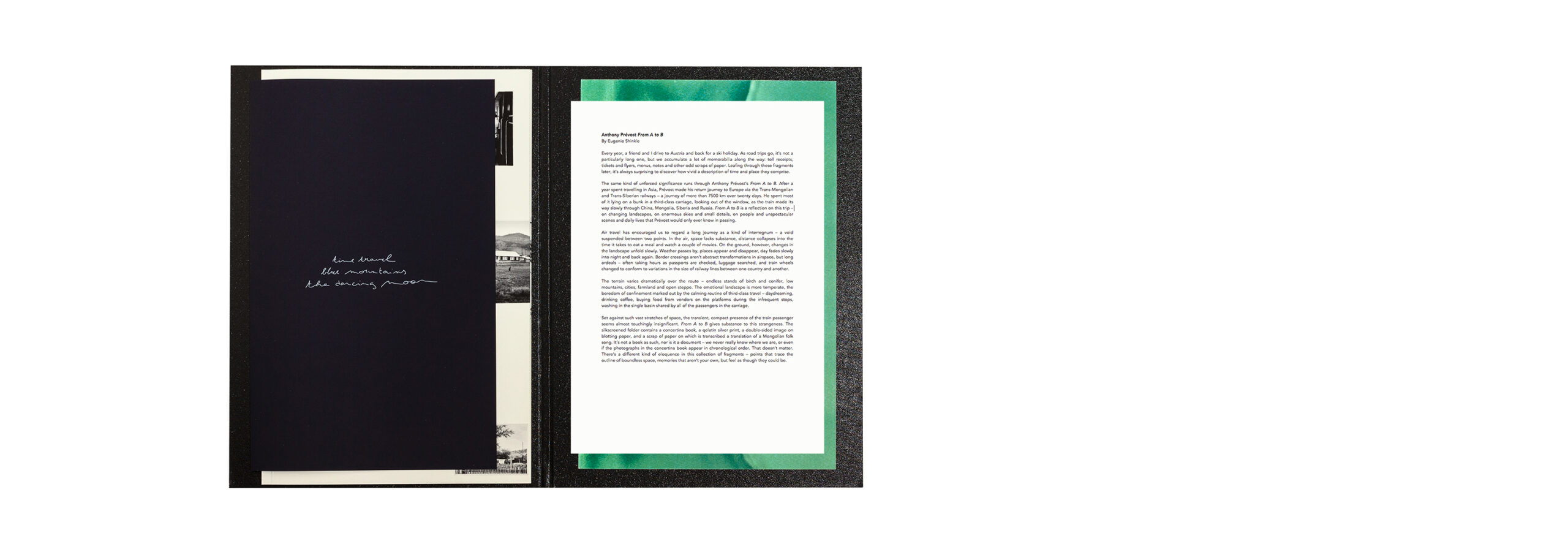

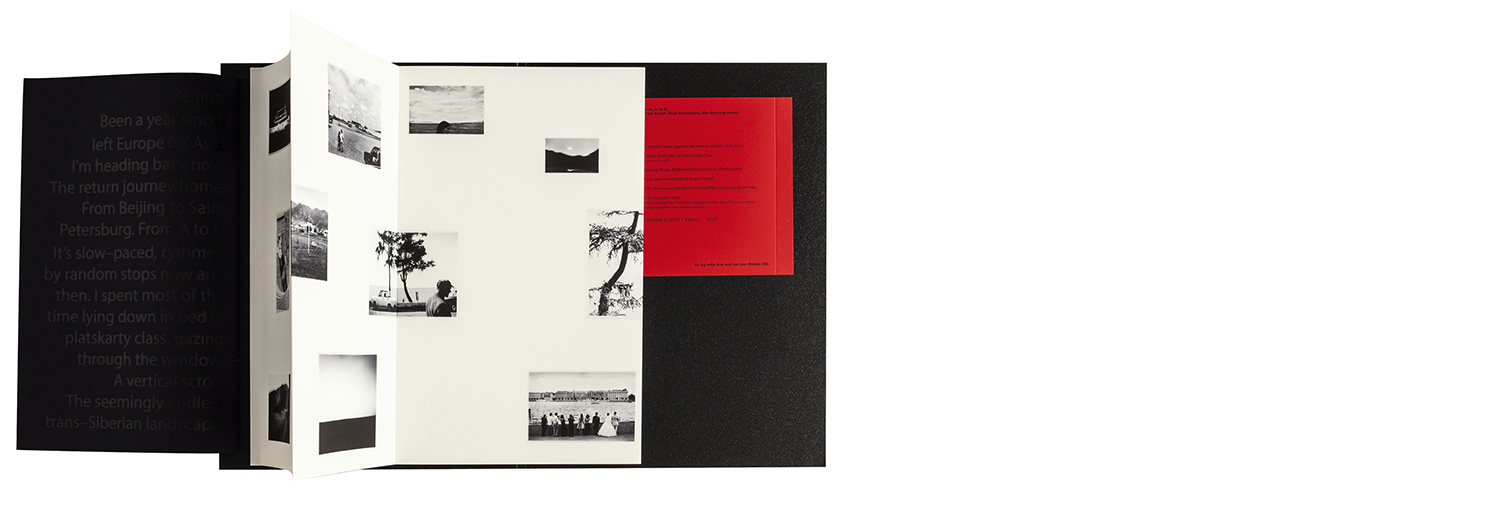

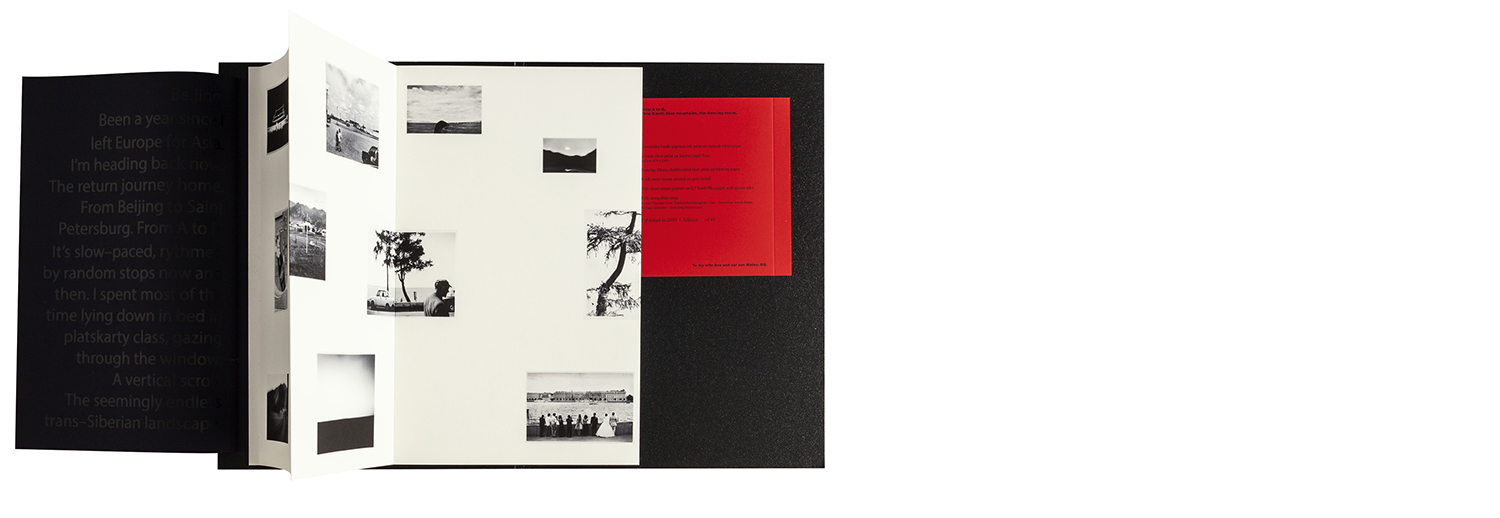

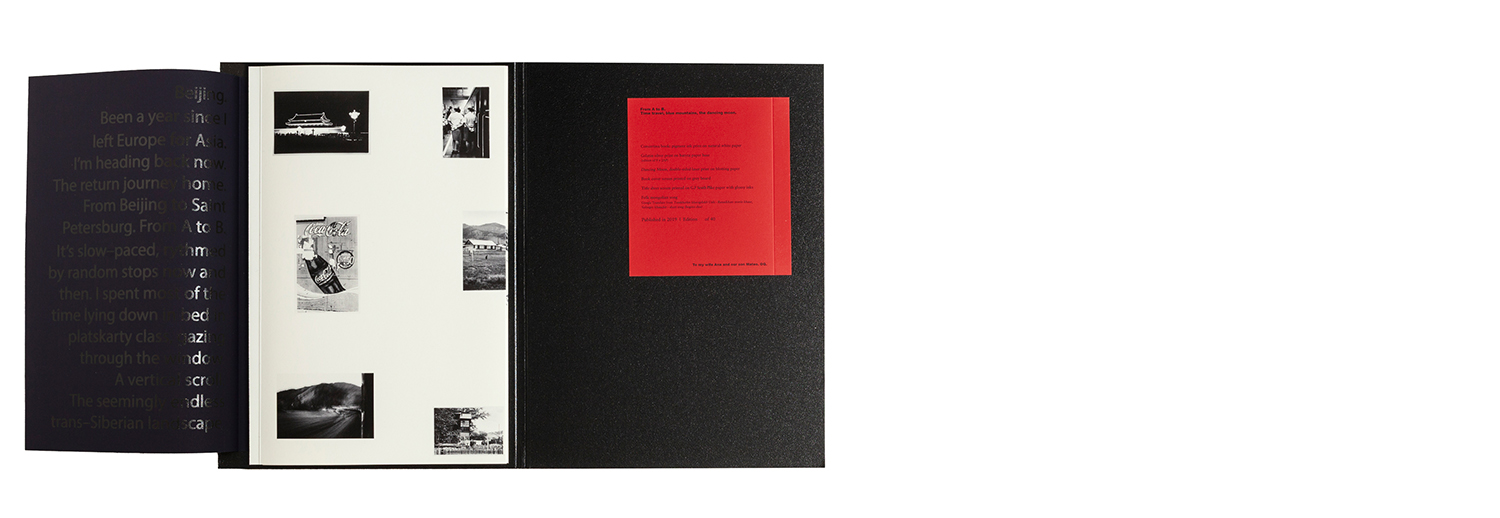

FC) The object we are looking at can’t really be labeled as a photo-book nor can it be described simply as a collection of prints. It is a rather fragile construction, held loosely together in a portfolio, containing fine art documents, objects, prints, facsimiles. The work “From A to B” resists traditional classification of the photographic body of work to categories like print or a photo-book and that is why I am drawn to it. Its materiality is elusive and in a way subversive. How do you think of these traditional forms of showcasing photography? Why not arrange a material like this, say in a more traditional format of a book?

(AP) Most traditional form of showcasing photography are purely a vehicle for the images to be viewed. Obviously the photobook has come a long way and some of them are tremendously creative in how they use the format.

However, books come with intrinsic limitations, not only in terms of narrative and sequencing but also in terms of paper and format. I’ve always been interested in how the photographs look once printed – the size, the paper, the print technique – it all influences how the image looks and what feeling it can evoke.

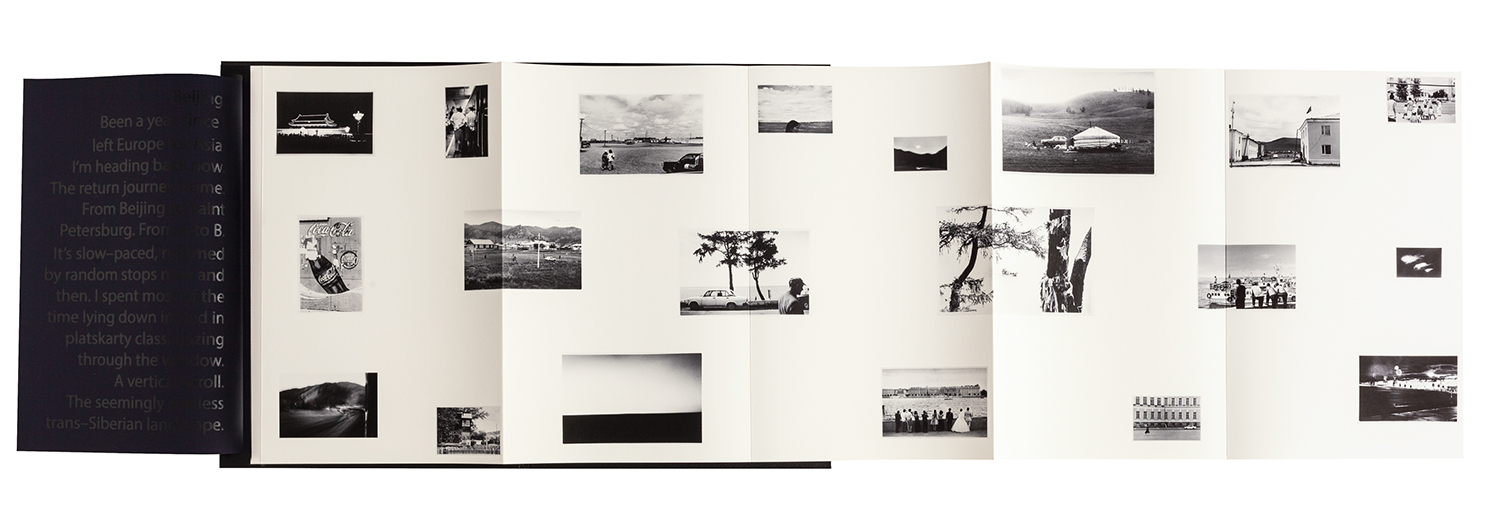

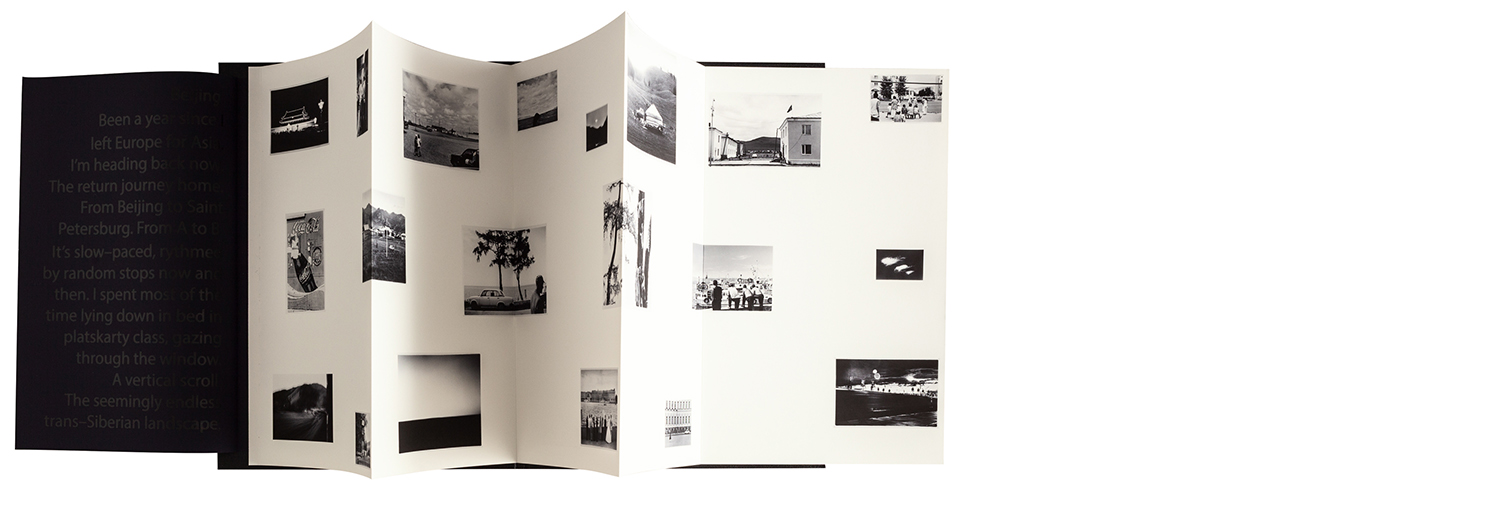

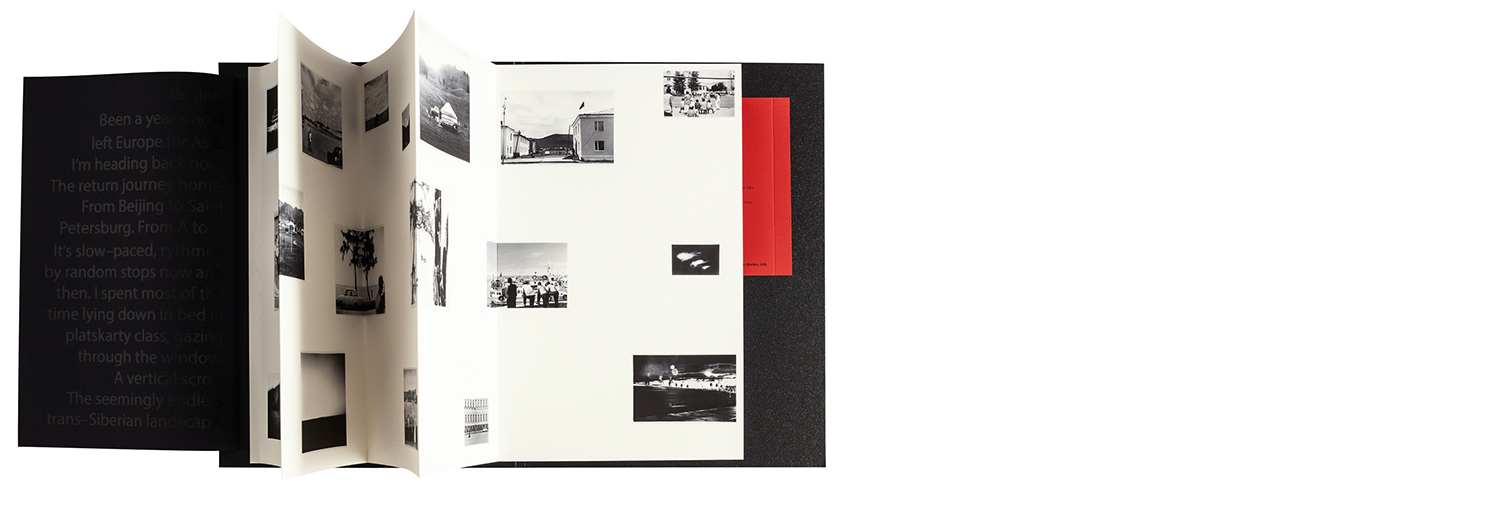

With “From A to B”, I wanted to free myself from those limitations and escape the page-to-page narrative. I was hoping to offer an active viewing experience – rather than impose a sequenced one. The idea was to create multiple ways to look at the work and hopefully creates an overall sensation through the accumulation of images and documents – something that would mimic the travel. I like the fact that it looks almost unfinished in its edit. That means there are more opportunities to interpret the work and the viewing experience can be different every time you open the folio.

The other reason for it to be that crafty is that I wanted to spend time making things (vs. editing on a computer), starting from scratch with raw materials, and let the manual process (and its imperfections) be part of the work.

(FC) The portfolio is composed out of different and eclectic fragments and poetic leftovers from the trip on Trans-Siberian / Trans-Mongolian railway. What was your route? And did you have a pre-set goal or did you engage in a sort of spontaneous wanderlust?

(AP) Like for most of the locals using that railway, my main goal was to go somewhere – not so much see anything in between. When I got into the first leg of the journey in Beijing, I had previously backpacked for over a year all around India, Nepal, South-East Asia, Japan and China. It was time for me to go back home – I was running out of money and appetite for traveling. Coming back by train to Europe seemed the most logical thing to me – after so much time away, and having traveled everywhere mostly through buses and trains, taking a plane felt inappropriate – I wanted to see and feel the distance, so the return would be less of a chock. Almost like the slow ascent needed for a scuba diver before resurfacing.

It took me about 20 days to go from Beijing to St Petersburg, with a few days in Mongolia, Siberia and Moscow. Moscow had always been the dreamed-end to my gap year. The train reached the station round 4am, by the time I was out, the sun was rising and I walked to the hostel, it felt pretty great.

Just like the whole travel through Asia, the Trans-Siberian journey was rather spontaneous. I bought the first ticket from Beijing to Ulan-Bataar and then bought the next legs when I'd arrive at my stops. This way I paid local fares rather than having to buy my whole ticket through a travel agency.

Once in St Petersburg, I took a train to Finland to visit a friend and a week later I was back in France.

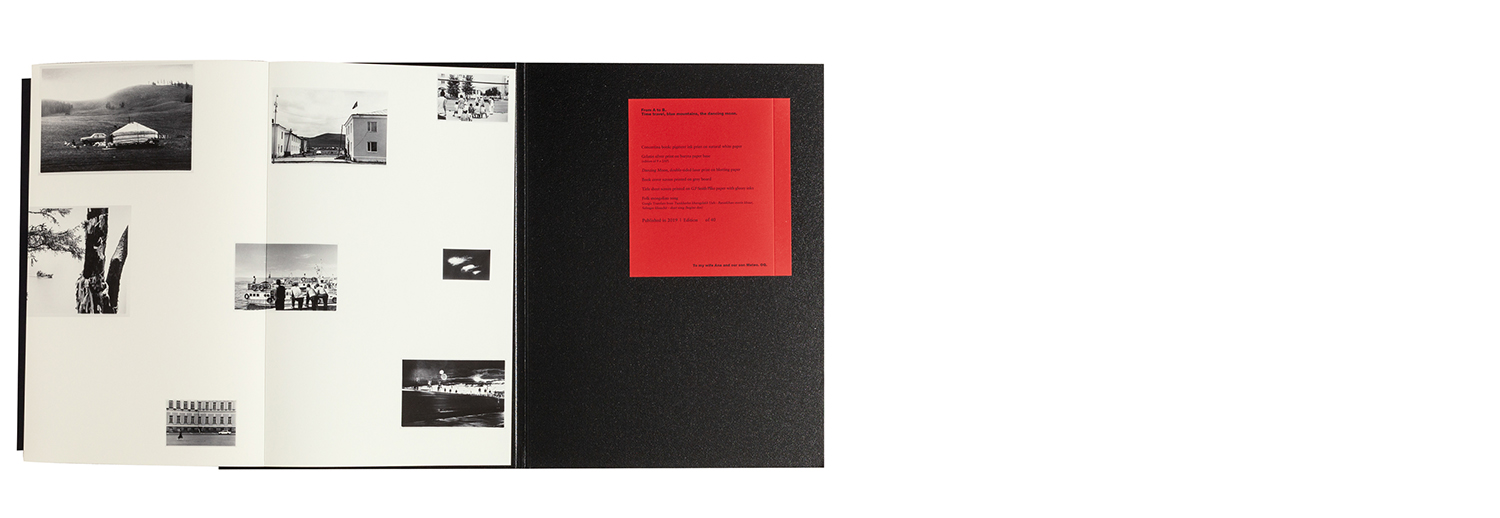

(FC) Looking at the images, pieces and fragments of your work, I am reminded of Chantal Akermans’s film “D’Est” (From the East) in which she silently observes the eastern (Russian, Polish and East German) landscape, people’s faces, manners, and eventually time itself. This anachronistic piece of travelogue also resists the traditional form of documentary storytelling, lingering on the in-between nature of the medium. Is your work “from A to B” somehow also about time or about its absence?

(AP) I’m glad you make the association with Akermans’s film.

I’m not sure I ever spelt it out this way – but time and its absence were very much in my mind both when I was in the train and when I designed the book.

When you travel for a year or so, your appreciation of time changes completely. First, because of the nature of traveling without deadline or destination, and second, because of the state of the means of transportation all around Asia – there’s a lot of waiting and guessing involved.

When I was in the train, I thought a lot about how my understanding of time had changed in the past year – and how it was about to collapse against the fast-paced and accurate timings of life in western countries. I was dreading it.

Long-distance train journeys are essentially about the absence of time – or at least about its arbitrary nature. This felt especially true due to the different time zones the Trans-Siberian trains cross and the fact that the schedules for departures and arrivals are always based on Moscow time, no matter where you physically are.

The journey felt pretty uneventful, long but pleasing. Other than the few stops now and then, I spent my time sitting or lying down in bed, gazing through the window, daydreaming, eating, reading and drinking instant coffee. That routine and the fact that there was nothing else to do were very calming.

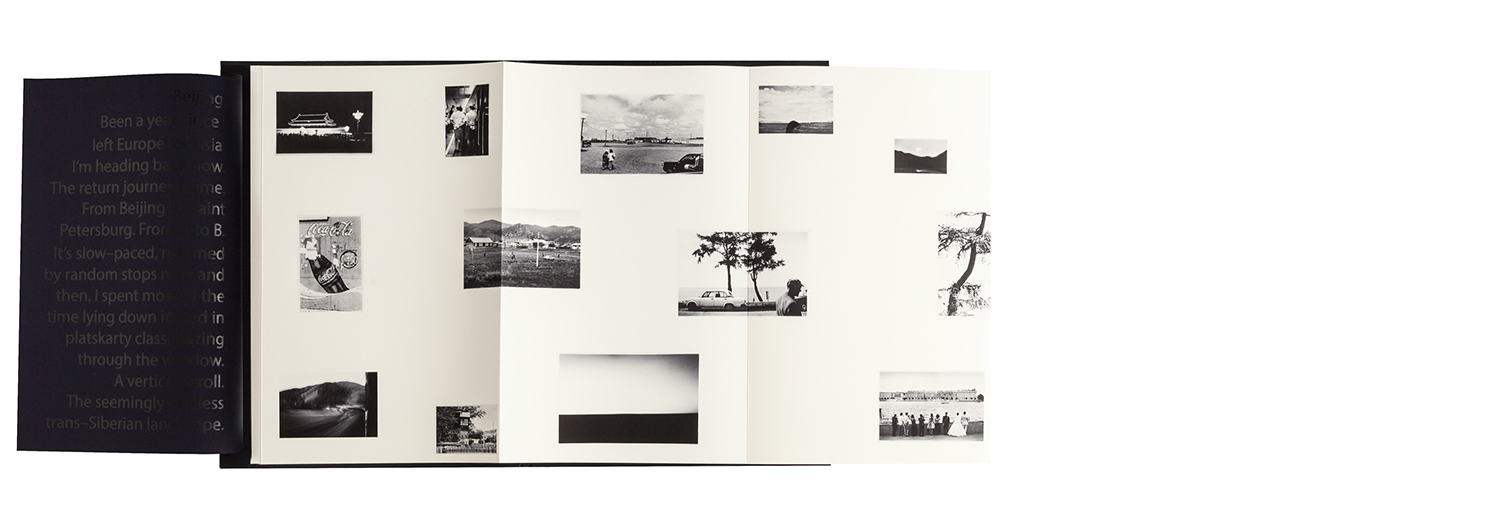

As I said, time was definitely something I wanted to evoke in the book and I tried to achieve that through the design. I’ve sequenced the images independently of their geographic and temporal locations and placed them all on the same sheet of paper without information or titles.

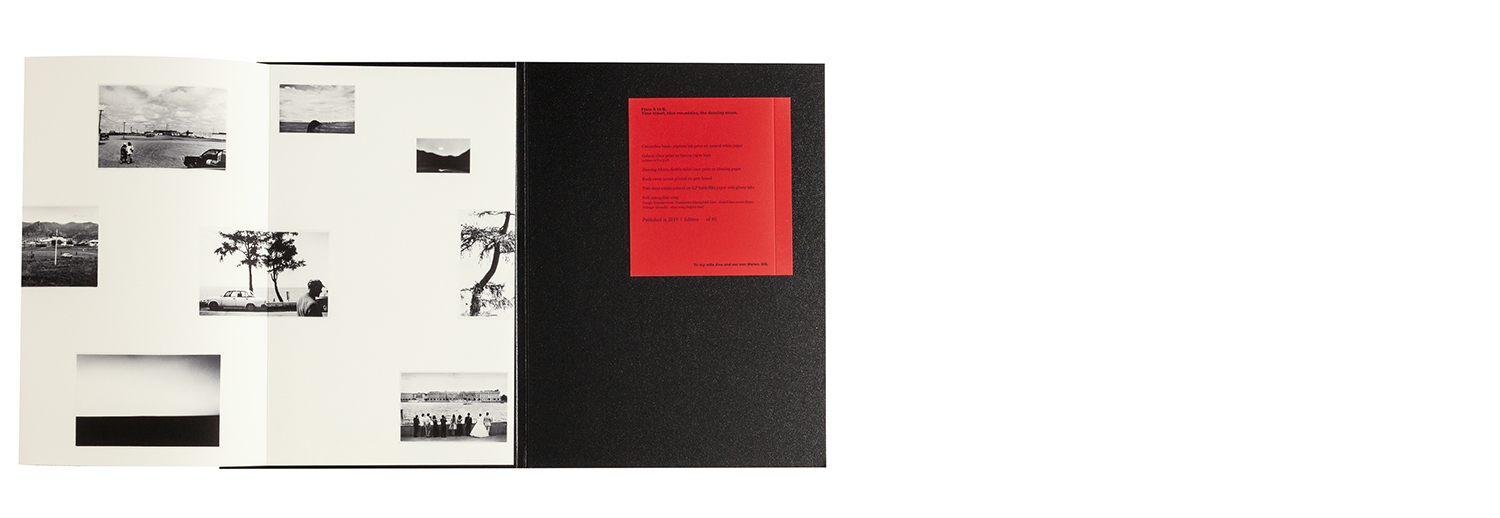

(FC) Your folio-book is like a dedication to slow looking and a praise of unhurried movement. The way you produce your images is also time-consuming. You work with traditional photography in the darkroom, and make silk-screen prints. Is this somehow conceptually inherent to the themes that you are exploring in your work?

(AP) As mentioned earlier, I really enjoy the craft behind making my own prints but I think the main reason I work with analog technic is that it leaves some space for the unexpected to happen. Unlike with digital printing, where every little detail can be controlled, analog technics bring along small imperfections that inevitably become part of the work. That’s something I embrace and that sometimes takes the work in a different direction.

With the use of those different print techniques, I was also looking to distance my images from the real world. Images are means of representation, but they are too often confused with the real. By using techniques such as screen-prints and laser prints, I was hoping to evidence that too.

(FC) Since Footnote Centre is a space dedicated to visual arts/ photography but also to essays, fiction and experimental book making, could you tell us what sort of books are on your worktable right now?

(AP) I have an 18-month-old boy – so unfortunately I am not reading as much as I’d like to! Instead I’ve been looking at a lot of children books and visually there are a few things about composition and colours to be learnt from them. I am actually quite inspired by how colours are used and combined to evoke emotions and this is something I’ve been playing with in my current work and research.

Despite not having much time, the two books on my desk at the moment are The Camera: Essence and Apparatus by Victor Burgin and In the Praise of Shadows by Junichiro Tanizaki.

+ FC (footnote centre)

AP (Anthony Prevost)